The Prime Minister of Czechia and the country’s second richest man, Andrej Babiš, plans to form a government supported by the communists. Consequently, for the first time since the fall of communism in 1989, the “Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia” (KSČM) has a real chance to influence the formation and policies of the new Czech government.

After the fall of authoritarian communist regimes of the Central and Eastern Europe in 1989, the majority of the communist parties ceased to exist. In Poland, Hungary, and Romania, the new governments banned these parties. In former Czechoslovakia, however, the President Václav Havel considered letting the communists compete in the elections as a more democratic option.

Throughout the years, the KSČM has consistently won between 10,33 % and 18,51 %. This party almost always finished third and never participated in any government. The other politicians were too worried about associating themselves with a direct successor of the former authoritarian communist regime.

In the most recent elections, the votes for the communists decreased significantly, and they ended up in fifth place with unusually low 7,76 % of the vote. It was the worst result in their history, presumably because many of their traditional voters, particularly those who are unemployed, decided to vote for a xenophobic and eurosceptic “Justice and Direct Democracy” (SPD) lead by half-Japanese Czech nationalist Tomio Okamura.

Despite the lowest results in the communists’ history, the Prime Minister has offered to allow them to participate in the government with his populist movement YES (ANO) and the Social Democrats (ČSSD) by supporting it in the parliamentary vote of confidence. It gives the KSČM significant leverage over the government’s formation and policies. How have the communists become highly sought after partners despite their poor electoral performance?

Vojtěch Filip, leader of the Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia (Photo credit to David Sedlecký and Wikimedia Commons).

Forming the new Czech government

The Czech President, Miloš Zeman, clearly favours Andrej Babiš. He has recently named him Prime Minister for the second time after Babiš even after failed to form a government with the Parliament’s confidence with his first attempt. Babiš, in turn, supported Zeman in the presidential elections earlier this year.

Babiš failed to form a viable coalition for the first time because many parties had issues with allegations that the police brought against him. They accused him and his conglomerate Agrofert of fraudulently obtaining of EU subsidies that were meant only for small companies. While he denies these allegations, many potential coalition partners emphasised that they did not want to cooperate with a Prime Minister who is currently facing criminal charges.

Nevertheless, the new leadership of the Social Democrats eventually decided to start negotiations with Andrej Babiš under certain conditions. Although the final decision depends on a referendum within their their party, the Social Democrats are likely to approve the coalition with Babiš.

Even with the Social Democrats, however, Andrej Babiš will not have enough votes in the Parliament to win the vote of confidence. As the other party was willing to back a government led by a politician facing criminal charges, Babiš asked the communists for their support. This means that while they will not officially enter the coalition government, they will tolerate it by supporting it during the vote of confidence.

The Communists’ views and demands

The communists currently possess a chance to shape Czech politics in a way that they have never done before. This could have significant implications for the new government’s policies.

Although the current communists democratised after the 1989, some of their prominent members still hold very problematic positions. For example, former Communist representative to the Chamber of Deputies Marta Semelová is notorious for her public support for Klement Gottwald, the Czech equivalent to Joseph Stalin who has executed many political prisoners during the 1950s on false pretenses. One of the victims of these show trials was Milada Horáková, a lawyer and a politician who became a symbol of the resistance against the totalitarian communist regime. Semelová denied that the allegations were politically motivated. She has also proclaimed, that the Soviet invasion in 1968 – a very sensitive topic for the Czechs – was not an occupation, but rather a “friendly help”.

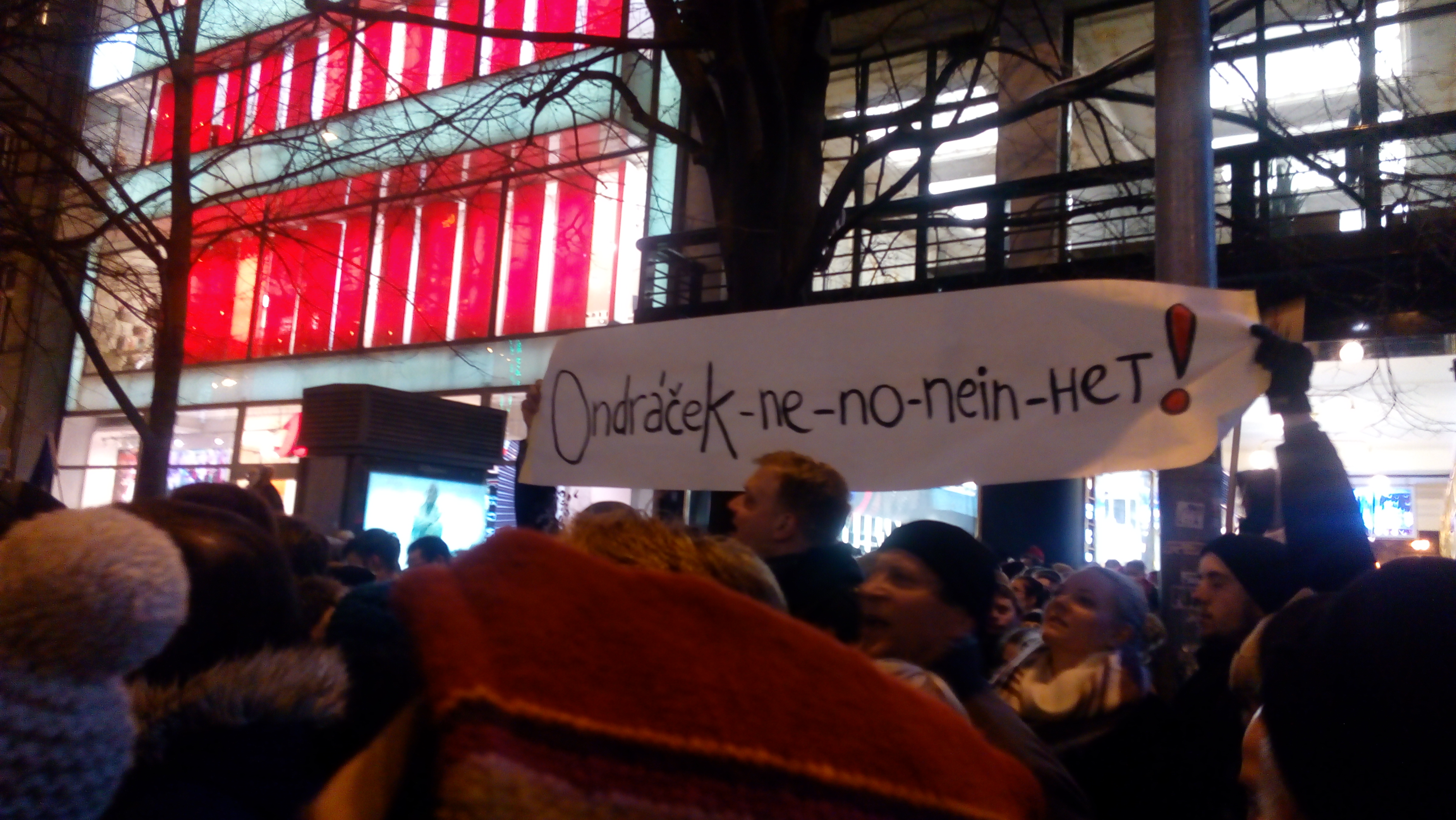

Similarly, Communist Deputy Zdeněk Ondráček participated in the attempts to violently quell the anti- communist student protests in 1989, and whose opponents call him a “puncher” to this day. He was also one of the Czech members of parliament who went to visit the separatist Donbas region in 2016 without notifying the Ukrainian government. He said he did not believe the “Western propaganda” and went there to see everything with his own eyes. On the same trip, he gave an interview celebrating Russia and Donbas separatists for a Donbas television station.

Demonstrators protest against Zdeněk Ondráček in March 2018 (photo from Wikimedia).

This pro-Russian foreign policy characterizes the views of many members of the KSČM. Josef Skála, a former Vice-President of the Communist party, often claims that the Czech Republic is the colony of the West and that the situation in the country was significantly better before 1989. Therefore, the Communists are mostly eurosceptic and opposed to Czechia’s membership in NATO.

These stances are reflected in the demands they have presented to Prime Minister Babiš. They proclaimed that they would only support his government if it does not expand the foreign missions of the Czech army. This might imply, among other things, the non-participation of Czech forces in NATO drills in the Baltics. Such developments of the Czech foreign policy could significantly harm its reputation among its allies in NATO and in the European Union.

Other demands of the communists involve certain personal changes within the government and their control over numerous Czech state companies. The rest of their plans will be revealed during the official negotiations once the Social Democrats will approve the cooperation in their referendum.

This prompted over 10 000 people in many Czech cities to protest in the streets against the planned coalition. The leaders of almost all opposition parties participated in these demonstrations.

Implications for Czech politics

The potential influence that the Communists may exercise over Andrej Babiš’ government is unprecedented, and could especially impact upon Czechia’s foreign policy. While their official demands will not become clear until after the results of the Social Democrats’ referendum, the potential implications for the new government should not be taken lightly.