Russia’s recent bailout of two major banks will cost the country billions of rubles. But the future of the Russian banking system, and its impact on the nation’s economy, is still uncertain.

Russia is finally emerging from a serious recession, with growth predicted for 2018. However, the recent rescue of B&N Bank and Otkritie Bank highlighted serious problems in Russia’s banking industry – problems that have not gone away following the bailouts, and could endanger the economic recovery if it doesn’t progress quickly enough.

A tale of two banks

Bank Otkritie FC, Russia’s biggest private lender in term of assets, started seeing huge cash outflows in June 2017. Then, in August, came a sudden ratings drop by Fitch.

“Otkritie, B&N Bank, Prosuyazbank and Credit Bank of Moscow are among the banks that have been subject to Russian media speculation in recent weeks, regarding the liquidity position of some and the potential knock-on effect on others.”

Fitch Ratings report, 18 August

The day before, Moody’s had placed Otkritie on review for a possible downgrade, citing increased financing of assets held by its parent company Otkritie Holdings, and volatility of customer deposits.

“Since mid-2017 and following the recent regulatory changes regarding the placement of non-state pension funds’ and state budget deposits, BOFC has experienced a significant outflow of customer deposits.”

Moody’s report, 17 August

It wasn’t long before the Central Bank of Russia (CBR) was forced to intervene. In late August, it became the biggest owner of Otkritie with a 75 percent stake, worth approximately US$51 billion. The strategy was to assuage depositors’ fears of losing their deposits, and stabilise the Russian banking system.

The takeover hurt Otkritie’s shareholders. Their ownership in the bank was reduced to a maximum of 25 percent, with the risk of seeing their investment wiped out completely. CBR deputy chairman Vasily Pozdyshev indicated that the bailout and Otkritie’s recapitalization would cost between US$4.34 billion (250 billion rubles) and US$6.96 billion (400 billion rubles), though the final tally could be higher. This bailout far surpassed the CBR’s rescue of the Bank of Moscow in 2011, which totaled 395 billion rubles. But another disaster was soon to follow.

Three weeks after the Otkritie bailout, B&N Bank, also known as Binbank and Russia’s 12th largest bank by assets, sought help from the CBR. Customers reportedly withdrew approximately 56 billion rubles from B&N in September 2017. Affiliated lender Rost Bank and other banks were rumoured to also require emergency financing from the CBR’s Fund for the Consolidation of the Banking Sector.

The five reasons behind Russia’s banking system troubles

1. Rapid expansion

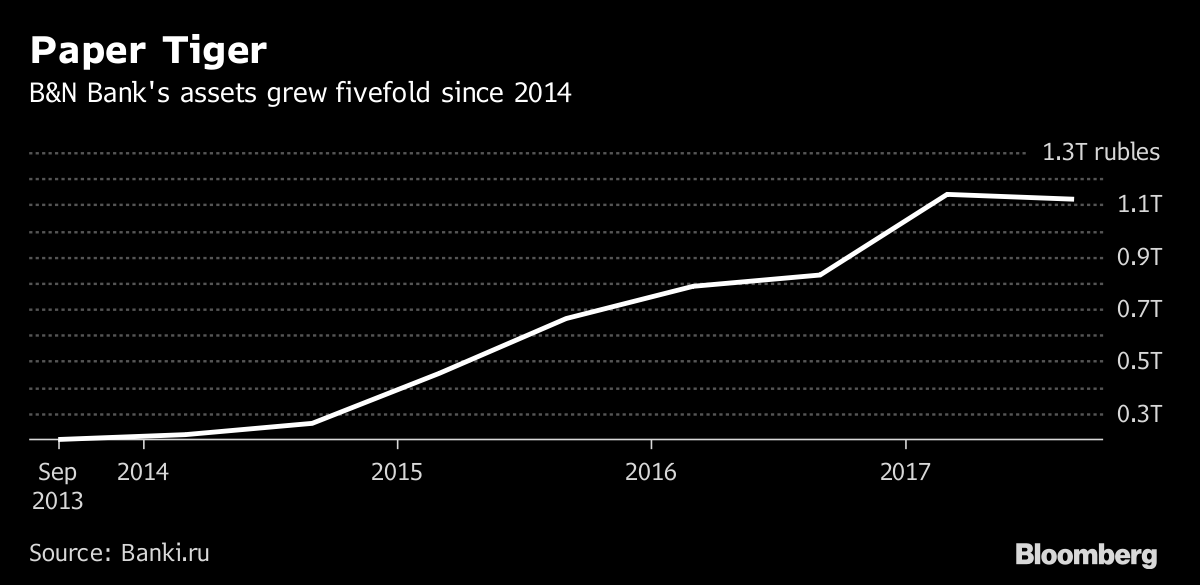

Otkritie and B&N both had a propensity for rapid expansion through acquisitions. Otkritie was permitted to grow at a very fast pace by purchasing Russian banking competitors such as Nomos, bailing out Rosneft Bank in 2014, while diversifying into non-bank companies. B&N had ambitiously expanded its operations after 2010 by acquiring smaller institutions such as Moskomprivatbank, SKA-Bank, and others, prior to making its biggest acquisition in 2016 by merging with MDM Bank, a large Russian lender. However, it turns out that the banks that B&N acquired had financial problems more serious than previously reported. B&N’s assets expanded fivefold in less than four years while also obtaining funds from the state in order to salvage smaller banks. As it turned out, Otkritie and B&N purchased big financial headaches that later came back to haunt them – and other Russian banks may be in similar situations.

2. International sanctions

US and EU sanctions over Ukraine probably did more economic damage than President Vladimir Putin is willing to admit – and Russia’s banking sector has not been immune. B&N’s situation was aggravated by the residual effects of an economic slowdown partly caused by the sanctions, and the rise of bad debt during the previous three years. Moreover, a key provision of the sanctions prevents Russian banks from raising financial capital on Wall Street. This prevents American investment firms and commercial banks from buying equity stakes or making long-term financing deals, and restricts Russian banks access to foreign capital. For example, Vnesheconombank (VEB)’s access to foreign capital was cut off due to the sanctions and looking at in foreign currency debt totaling US$16 billion. A bailout of VEB could cost the Russian government at least US$18 billion or 1.3 trillion rubles.

3. Sharp decline in oil prices

Under Putin, Russia has effectively become a petrostate, heavily dependent on oil as a source of revenue for the government. The higher the price of oil, the more rubles the Russian government can deposit into state and private banks resulting in a greater influx of financial capital. However, the price of oil has dropped in recent years as the market has become awash in oil due to increased uses of clean energy. This has lowered the amount of funds the Russian government can put into the nation’s banks and, therefore, hurt their cash flows. Compounding the problem is that Russian banks made loans to the nation’s oil companies under the assumption that oil prices will rise.

4. Ruble devaluation

The Russian ruble has lost value in recent years leading to a lack of liquidity for the nation’s banks. In an attempt to stabilize the ruble exchange rate, the Bank of Russia raised interest rates to 17 percent from 10.5 percent. But this move was not enough and the ruble devalued further. The combination of a depreciating ruble and rising inflation has made it more difficult for large, and especially small Russian banks, to remain liquid. As many Russian banks rely on cash as their main asset, the ruble’s depreciation causes them to lose value and have to acquire more funds. This means increased borrowing at possibly higher rates or seeking government bailouts so they can stay solvent.

5. High number of bankruptcies

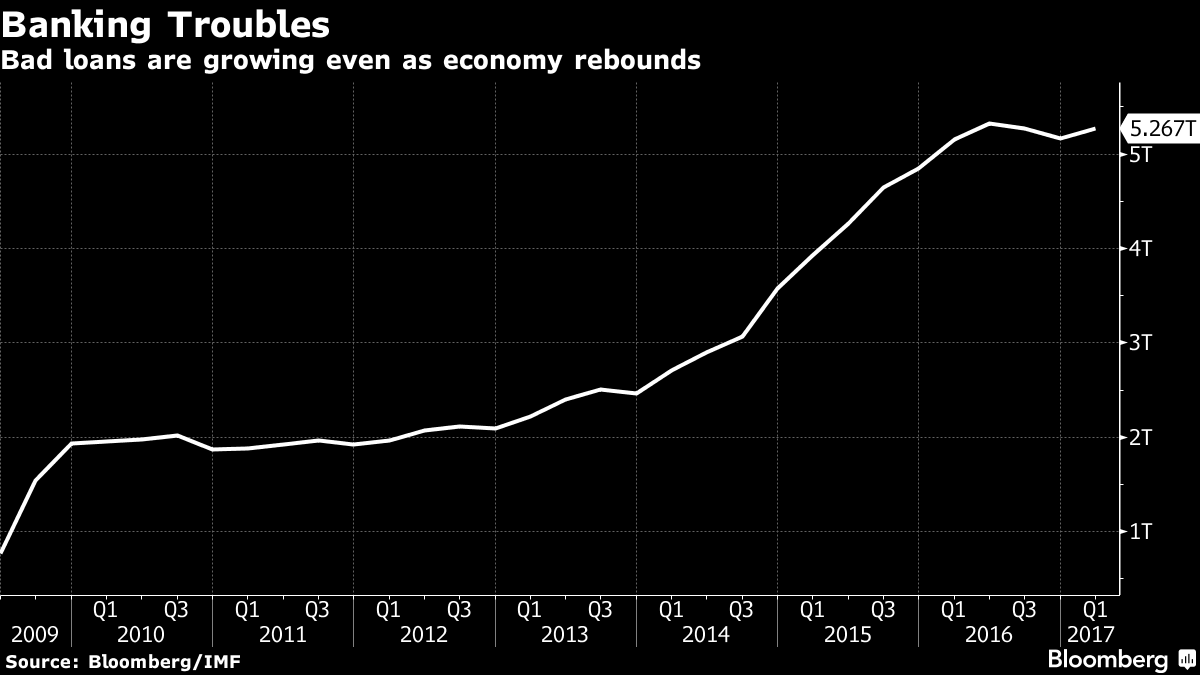

As if Russia does not have enough financial headaches, the country has seen a wave of bankruptcies among banks in recent years. Adding to these closings is the increased amount of non-performing loans (NPLs). For example, NPLs went from 6 percent in all of 2013 to 9.2 percent in the first quarter of 2016. The higher the number of NPLs, the greater the chance of bankruptcies among Russia’s financial institutions. Officially, these NPLs make up about 10% of all loans. However, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimates the true level of bad loans could be closer to 13.5%. Either way, many Russian banks are facing financial catastrophe. In order to stem the tide of these bankruptcies, between January 2014 and mid-2016, the CBR revoked 214 bank licenses and placed 28 banks into open bank resolution, using public moneys totaling 1.1 percent of Russia’s GDP.

Persistent risks

“The bailout was good for investors, probably bad for the system. They prevented the Lehman effect in the Russian banking system and created a too-big-to-fail mentality. How many other banks in Russia with the same sort of problems will need a bailout soon?”

Dmitri Barinov, Portfolio Investor, to Bloomberg News

In September there seemed to be a glimmer of hope when Fitch revised upwards the outlooks of 23 Russian banks. Tellingly however, this was off the back of a sovereign outlook upgrade, meaning that it wasn’t the strength of the sector that prompted the change, but the allegedly improved ability of the state to bail them out if required.

Even that capability is in question. Russia is probably in worse financial and economic shape than its policymakers and leaders are willing to admit. It’s well known but worth repeating, that Russia has become too dependent on oil at a time of sustained low oil prices. Oil was supposed to be Russia’s source of financial capital that it could put into its banks and always provide them with the cash flow they needed in good and bad economic times.

But now Russia is walking a financial tightrope that could impact the nation’s banking system for years to come. Unless Russia makes a strong economic recovery in the near future, its banking sector could see more hard times that the CRB will not have the power or resources to bring under control.