Australia now is growing impatient in cementing a free trade agreement (FTA) with China. In early October, new Australian Prime Minister Tony Abbott indicated his intention for securing a watered down deal.

Negotiations on an FTA date back to 2005. But after nineteen rounds of negotiations, a deal has still not been reached. Abbott’s predecessor, Kevin Rudd, revived the moribund FTA talks after a phone discussion with Chinese President Xi Jinping this June.

The most recent talk made “good progress” on three fronts: sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS); technical barriers to trade (TBT); and trade in services. Other “constructive discussions” included those on trade in goods, rules of origin, customs procedures, investments and dispute settlement. However, this is a very broad and vague description of the process underway. In fact, no clear sign of an agreement on the agriculture sector and investments, which are the key focal points, has yet emerged. Beijing is concerned about opening markets to Australian food, while Australia is reluctant to lower the threshold for Chinese investments. Although it is still too early to predict the outcome of negotiations, a watered down deal seems most likely.

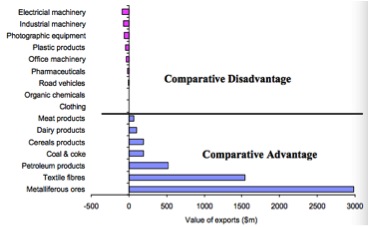

A full-scale FTA between the two countries will do more good than harm, in general. The original feasibility study found an FTA could boost GDP in Australia and China by 0.012% and 0.006% in the following year. However, winners and losers would appear after the agreement, divided by industries. Chart 1 shows the comparative advantages of some main industries in China and Australia in 2003. China has developed substantially since then, but this would only strengthen its 2003 comparative advantage in manufacturing. Australia has always been a big supplier of China’s energy sector. Its advantage in agriculture is also outstanding.

Chart 1: Australia’s comparative advantages and disadvantages with China

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics trade data for 2003 and the Economic Analytical Unit of DFAT

Interest groups’ submissions to Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) since 2005 are also good indicators of FTA’s potential impact. According to these submissions and feasibility studies, interests have indeed been aligned along the industry divides of comparative advantage and disadvantage. For instance, the Federation of Automotive Products Manufacturers was not optimistic about removing tariffs, as the effect would be negative for Australian component companies. Dairy Australia, however, asked for “removal of all tariffs on all dairy product lines” and detailed provisions on SPS. Likewise, the Australian Wool Processors Council urged China to cancel its differential tariffs and VAT system to give semi-processed wool a fair shot. China is Australia’s largest customer for wool, the majority of which is in greasy form. Opening up the semi-processed wool sector would badly hurt China’s wool processing industry.

The sentiment for an FTA has been strong, among both industry groups and governments. China’s FTA with New Zealand has aroused jealousy from Australian investment seekers and farmers. It seems the race-to-the-bottom mechanism is helping China expand its trade influence in the Asia-Pacific region.