ECB and Germany must learn to love inflation for Eurozone to grow

Even though the Eurozone is teetering on the edge of deflation, the ECB will not lower its rates.

The European Central Bank’s (ECB) message to markets in the last year has been clear: it will do anything in its power to stabilize the Eurozone. Anything, that is, except delivering on its inflation target. Eurozone inflation – or perhaps more appropriately, non-flation – was just 0.5% in March, the lowest level since 2009.

After hearing this news, the ECB took very little action. Rates will remain at 0.25%, letting non-flation settle in for another month. Non-flation looks even worse in the Southern European countries hardest hit by the Euro crisis. Prices in Spain, Greece, and Cyprus are now falling, as is the prospect of these economies becoming healthy anytime soon.

With the debtor-creditor power divide in European economic policy, it is clear that if the ECB is to act more aggressively to stop non-flation, Germany will have to sign off. The problem is, of course, that Germany despises inflation. That may have begun with hyperinflation in the 1920’s, but it continues today with Germany’s reliance on exports. Higher inflation will raise German wages, which the country has worked for twenty years to keep relatively low. In turn, it will hurt its export competitiveness and huge trade surplus, however, the costs for the Eurozone of non-flation are much greater in the long term.

There has been some confusion in reporting on the ECB about whether deflation, or non-flation for that matter, is really a bad thing. But there should not be any confusion at all. A deflationary spiral could turn the Eurozone into a mammoth version of Japan, which has been stagnate since deflation began in the 90’s.

Deflation makes each Euro worth more the longer a consumer holds onto it. Once a country falls into deflation, bad expectations about the economy become a self-fulfilling prophecy. There does not even need to be deflation for this to happen. Spending will be depressed as long as inflation is lower than the optimal 2% the ECB is supposed to target.

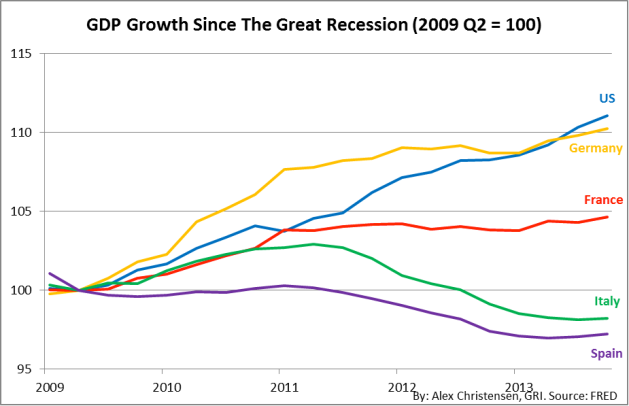

With growth rates in most European economies still recovering from the most recent recession, letting deflation take hold would be devastating. It may be understandable why Germany is less sensitive to deflationary pressures, since it has grown roughly as fast as the US in the last 5 years (see chart). But for the other largest European economies, growth has been slower and deflation is more of a threat.

Worse yet would be deflation in the face of the €500b of bailout loans the peripheral Eurozone countries received during the Euro crisis. Debt is the worst thing about deflation because the burden of loans only becomes greater. The budget conditions attached to the bailouts are already poised to hold down GDP growth in PIIGS economies, but deflation would be much worse.

As wages fall, tax revenues will fall and the debt-to-GDP ratio will accelerate upwards. Ironically, those falling wages will mean that Eurozone countries import fewer goods from Germany and the German economy will be affected as well.

Germany’s leadership in the Eurozone has emphasized two things: reigning in government debt and keeping inflation low. Those two goals are contradictory now that non-flation and deflation have set in. Politically, however, acknowledging that one of these policies must be given up will be difficult. Look at Germany’s response to EU and US criticisms over its reliance on exports: they failed to recognize that keeping the world’s highest trade surplus could be hurting European growth.

Reading through the comments of Der Spiegel, another huge political problem comes to light: the German public already believes that it is paying to let southern European countries off the hook and it does not want that to happen again. This creditor-debtor relationship, and particularly the bitterness felt by the creditor countries, is now the biggest risk for economic recovery in Europe. A side effect of the Euro is that there is only one monetary policy for all 17 countries, despite vastly different priorities among them.

Naturally, the largest creditor country, Germany, has become the biggest influencer of monetary policy. The result is an ECB that works very well for Germany, but not nearly as well for the PIIGS.

There is some hope that the ECB will change its tune. President Mario Draghi revealed that the ECB discussed – but did not vote on or implement – more quantitative easing and negative interest rate bonds at its latest meeting. Executive Board member Benoit Coeure told the French press that there may be a need to lower interest rates. Both statements indicate that the ECB is well aware of the non-flation problem on its hands.

The trouble is, as it has been all too often the case in the past 5 years, that the ECB is too late to realize it. These issues are not new revelations, but the ECB appears to have only begun discussing how to combat them now, after prices fell in the Eurozone’s 4th largest economy for 3 of the last 6 months. Overcoming the tightly-held views of the most influential country in the Eurozone is difficult, however, and now it looks increasingly likely that the ECB is, at the very least, moving towards the aggressive policies it needs. Late is better than never.