ICJ grants Peru more ocean, maintains Chilean fishing grounds in ruling

On January 27th 2014, the International Court of Justice compromised in determining the maritime boundary between Peru and Chile, granting rights to key fishing stocks.

Ruling on a case filed by Peru in 2008, the International Court of Justice brought a longstanding dispute between Peru and Chile to a close and gave each country rights over crucial fishing stocks. Peru had asked the court to delineate an equidistant maritime line between the two countries while Chile argued that a border already existed along a latitude line.

Compromising between the two positions, the ICJ gave Peru exclusive economic rights over a wider swath of the Pacific ocean, while maintaining Chilean rights over a key fishing area close to shore. Due to the Humboldt Current in the Pacific, the waters off the coasts of the two countries are rich with fish including anchovy, tuna and bonito. In presenting their case to the ICJ, Peru claimed that 18-20 percent of the world’s catch comes from this particular area, and some estimates place the value of the annual catch at $200 million.

By defining the maritime border between the two countries, the ICJ’s ruling helps to stabilize a growing economic relationship and could foster further cooperation.

A new maritime border

In 1879, Chile fought Peru and Bolivia in the War of the Pacific, winning Peruvian territory and the entirety of the Bolivian coast. A failure to follow up on the peace treaty left the maritime boundary ambiguous.

Despite subsequent declarations and agreements, Peru believed that no formal maritime boundary had been set between itself and Chile. It sought to gain a larger exclusive economic zone by asking the ICJ to draw an equidistant line running southwest from the coast out into the Pacific. Chile argued that agreements made in the 1950s had already set a boundary running due west from the coast on a parallel line of latitude. This would have granted Chile a larger zone, infringing on what Peru considered its home waters.

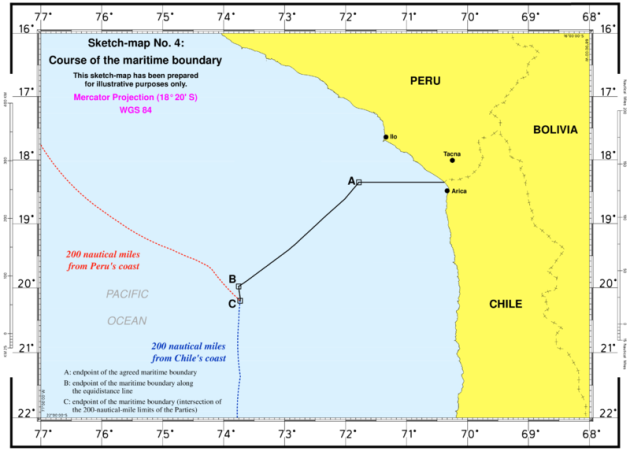

In a 10-6 vote, the ICJ drew the border following this line of latitude west for 80 nautical miles. At that point in the ocean, the border turns southwest following an equidistant line until it reaches the 200 nautical mile limit of Chile set by the UN Convention of the Law of the Sea (see map). In configuring the border this way, the ICJ recognized Chile’s historical claim, but also granted much of Peru’s request. Peru now has rights over a larger area of the Pacific but Chile maintains control over key fisheries near the city of Arica.

Why it matters

Following the ruling, Peru’s President Ollanta Humala declared, “we have won more than 70 percent of our entire demand.” On the other side, Chilean President Sebastian Pinera called the ruling a “lamentable loss of our country.” Reports indicated that many Peruvians felt it was a victory for their country while Chileans in Arica demonstrated against losing access to fishing stocks further out at sea. Although Peru might appear to be the winner, the incoming Chilean president noted that most of Chile’s fishing occurs within areas that the ICJ declared to be Chilean waters.

The ruling cements an increasingly profitable economic relationship. Annual bilateral trade has surged since a free trade agreement was implemented in 2009, from $500 million in 2006 to $4.3 billion currently. Both countries are members of the Pacific Alliance with Colombia and Mexico. Chilean firms have invested over $13 billion in Peru, and Peruvian investment, although lower, has also increased.

In a preview of the ruling, the Center of International and Strategic Studies summed up the impact: “In the simplest terms, then, the successful implementation of the ICJ’s ruling could keep bilateral economic relations on their already promising trajectory.” By codifying the boundaries, the decision also makes area trade more stable and rooted in a rules based system.

The growing economic relationship, along with developing people-to-people exchanges at the border could help heal tense feelings stemming from a historic conflict between the two countries. Yet, the ICJ did not determine the precise geographic coordinates of the new boundary. It is up to Peru and Chile to do so cooperatively, after the formula laid out by the ICJ. This could take some time, but Peru and Chile should be commended for supporting international mediation in their dispute. The ICJ’s ruling looks set to reduce long simmering tensions, paving the way for further economic growth.