Shinzo Abe celebrated his first year as Japanese Prime Minister in December, which also marked one year with Abenomics. For many, this will be a dismal anniversary, as the latest figures are not particularly encouraging. However, the game is not over yet.

On December 26th, Shinzo Abe celebrated his first anniversary as Japanese Prime Minister. His hotly debated policy mix, ‘Abenomics’, consisting of expansionary monetary and fiscal policies as well as structural reforms, is still in force and has so far produced some encouraging results. Yet, the latest GDP figures show that economic growth slowed in the third quarter of 2013, suggesting sustainable development towards the ‘re-creation’ of a durable economy is still far from reality.

The Bank of Japan (BOJ) has already implemented monetary easing, which constitutes the first arrow of Abe’s policy package. With the admittedly challenging inflation target of 2 percent, policymakers have aggressively attempted to address the country’s deflation malaise. So far, the project has been considered successful, with the yen having declined by 20 percent against the dollar, reaching a ¥103 level on December 15th. Moreover, according to the monthly economic report released by the Japanese Ministry of Finance, domestic corporate good prices rose at a moderate pace and the core consumer price index, excluding food, rose 0.9 percent from the previous year.

On the fiscal front, the second arrow of Abe’s policy mix, an expansionary policy with a generous stimulus package of 10.3 trillion yen for infrastructure projects and stimulation of private investment seems to have boosted the economy. In fact, Japanese economy grew at a pace of 4.3 percent from January to March 2013 and 3.8 percent in the second quarter. Other main economic indicators such as private consumption, employment and corporate profits are also moving in an upward trend.

Nonetheless, the latest data from the Japanese Ministry of Finance indicate that the period of euphoria is probably over. The economy grew an annualized 1.1 percent in the third quarter marking a decline on the pace of growth of 2.7 percent from the previous quarter. At the same time, the national government released figures on the country’s current account balance, which shows a deficit of ¥128 billion.

Abenomics doubts flared up at once and skeptics, feeling more confident than ever, started stressing the potential risks and challenges of the policy mix. Among those, low levels of business investment and capital expenditure rank highest. “Since taking office last December, Abe’s stimulus efforts have barely dented a slide in private-sector investment at home, but they have done wonders for accelerating Japanese investment elsewhere in Asia,” say W. Arnold & O. Spiring.

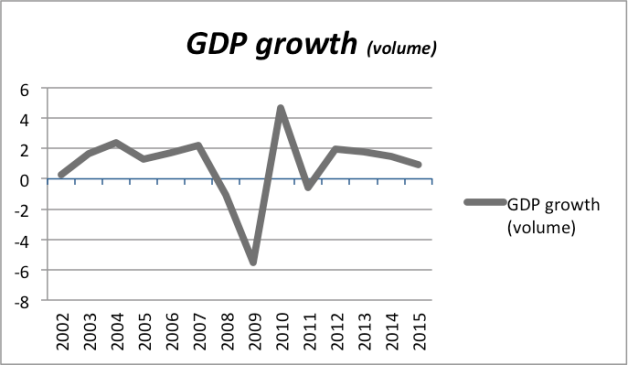

Fears on the reduction of private consumption are gaining ground as the government announced the increase of the consumption tax rate from 5 to 8 percent from April 2014 onwards. Although a ¥5 trillion stimulus package has recently been approved to partially compensate for the negative effect of the tax, increasing wages could be a more efficient way to offset the impact of the measure. What is more, OECD economic projections show that the Japanese GDP is expected to slow further until 2015, enhancing existing perceptions that the honeymoon for the Japanese economy is over (chart below).

But is this really the case? There is no straightforward answer.

For those who advocate that low business investment is the Achilles heel of the Japanese economy that Abenomics cannot successfully address, the latest data released from the Ministry of Finance serves as a counter argument showing that for the second quarter of 2013 business investment in all industries has increased by 1.4 percent from the previous quarter.

The same upward trend holds for industrial output and machinery expenditure. Of course the above figures are not sufficient for someone to argue for the efficiency of Abe’s policies. These Keynesian-inspired measures, albeit capable of boosting the economy in the short-term will guarantee neither higher competitiveness in the long-term nor sustainable development. And here comes the third arrow of Abe’s policy mix, the hardest task, ‘structural reforms.’

The need for structural reforms is stronger than ever if Abenomics is to succeed, and the labour market is first on the list. Deregulation of the secure Japanese job market will render domestic businesses more competitive on the international arena and increase foreign investments. Yet, Prime Minister Abe although having acknowledged the necessity of such a reform, does not seem ready to promote its implementation directly.

Regarding the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), the decision for Japan to participate had been a promising one in terms of revitalizing the economy. But during the latest round of negotiations, which took place in Singapore, stakeholders failed to reach an agreement, because Japan insists on the protection of several sensitive agricultural products. Given that abolishing agricultural protectionism will reduce Abe’s popularity within rural voters such an action, although essential for negotiations to proceed further, poses a considerable political cost.

That said, in defiance of those stuck with austerity, stimulus policies did well in boosting the economy in the short-term, but whether the country will remain a leading economic power depends on the government’s determination to implement the required reforms. To put it differently, the honeymoon for Japan is not over yet but the road to success will be long and bumpy, so the question remains: will Abe take the political cost?