Lead, Engage and Balance: U.S strategic options for integrating China

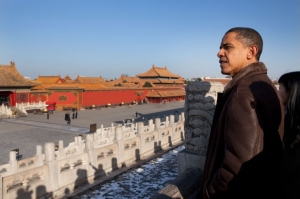

A strategy of sustained U.S. leadership as the best option for China’s peaceful integration in the global system. Does China wish to be integrated? (Photo credit: Wikimedia)

The Asia-Pacific’s place at the forefront of economic growth relies on the maintenance of order that may be inhibited by the weakening of U.S. unipolarity and the rise of hegemonic challengers, principally China. Now the world’s second largest economy immediately ahead of Japan and behind the United States, China’s rapid economic transformation supports increasingly impressive military capabilities. How the international system and the United States adjust to the rise of Chinese power will be critically important to the future of the Asia-Pacific region, and in turn global stability and prosperity. As the primary security benefactor and a major beneficiary of both regional and global security and economic stability, the United States must pursue a consistent strategy supporting the peaceful integration of China into the global system.

This piece examines strategic possibilities for the Asia-Pacific region in response to China’s rise, reviewing the arguments of two seminal papers that address the Asia-Pacific’s changing regional architecture: Joseph Nye’s East Asia: The Case for Deep Engagement and Charles Kupchan’s After Pax Americana: Benign Power, Regional Integration, and the Sources of a Stable Multipolarity. This piece asserts—and defends—a strategy of sustained U.S. leadership as the best option for China’s peaceful integration in the global system while maintaining regional and international stability.

China’s Peaceful Integration: Strategic Options in the Asia-Pacific

When asked what his “number one” recommendation was for China policy, assistant Secretary of State for Asia and the Pacific Kurt Campbell advised that, “Good China policy is best done when embedded in a strategy for Asia.” As such, strategies for China’s peaceful integration should be examined in context of a broader Asia-Pacific strategy. In East Asia: The Case for Deep Engagement Nye notes five dispassionate possibilities for an Asia-Pacific strategy. Each of these strategic possibilities would have a direct bearing on the peaceful integration of China into the global system.

The first potential strategic response to the rise of China is to withdraw from the region and pursue a hemisphere or Atlantic-only strategy (Nye 92). Such an option would give China hegemonic breathing space, allowing it to fill the gap and ideally expand peacefully. There are numerous reasons why this is an impractical strategy—principally the risks of an aggressive vacuum of power—but the core impracticality is a result of this option’s sheer disregard for the extensive and growing American interests in the Asia-Pacific. Four U.S. states border the Pacific while and Hawaii is surrounded by it. Three Pacific island territories—Guam, American Samoa, and the Commonwealth of the North Marianas—are closer to Asian capitals than to Washington and would be easily impacted by the power politics of the Asia-Pacific. American trade with the Asia-Pacific region stood at nearly $400 billion and accounted for three million United States jobs at the time Nye wrote his paper. This impact has only increased and cannot be ignored.

The second potential strategic response to the rise of China is for the United States to maintain its activity in the Asia-Pacific but withdraw from its alliances (Nye 93). This strategy would let normal balance-of-power politics take the place of American leadership while leaving the United States to be more directly impacted by this politics. Ostensibly, this would make the United States and its former allies less of a threat to China’s rise, allowing peaceful integration. However, the vacuum of power would likely lead to a regional arms race as states attempted to deter the growing capacities of an ascendant China. While the United States would no longer have to defend its former allies, it would have to balance the new and enhanced forces that would be developed by Asian actors. The United States would absorb these costs without the receiving the benefit sharing of its Asian allies, while ignoring and wasting the valuable investments made in existing relationships. Ultimately then, this strategy would weaken U.S. interests and could endanger China’s peaceful integration.

The third potential strategic response to the rise of China is for the United States to create loose regional institutions to replace its structure of alliances (Nye 93). This would ostensibly link together the states of Asia, lessening the risk of conflict between an ascendant China and other actors. However, the reality of this is limited by historic enmities that antedate the Cold War and have not been overcome; one only has to look to the recent, growing conflicts over the Senkakus/Diaoyu and Takeshima/Dokdo and the swift application of historicity and nationalism to confirm the tangibility of this issue. Such a weak institution built on historical conflict would neither functionally allow the engagement nor apply the coercion threat necessary to maintain stability in the region and aid in China’s peaceful integration.

The fourth potential strategic response to the rise of China is the creation of a NATO-like regional alliance (Nye 94). Ideally this alliance would maintain stability in the region, binding allies and serving as a soft threat to potential enemies; this would hopefully allow the maintenance of security in the region, propping up the Asia-Pacific system as China takes a new place on the regional stage. The mistake here is that such an alliance would be seen as aimed at China- by itself the alliance runs the risk of appear as coercion only, and as a prejudice against a rising China which still has the opportunity to integrate. Such a strong containment strategy would be difficult to reverse, with engagement-less enmity becoming a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Forward Presence, Engagement, and Balancing: An Asia-Pacific Strategy for the Rise of China

The strongest option in support of the peaceful integration of China is an Asia-Pacific strategy of U.S. leadership supported by both the engagement and balancing of China. In pursuing this strategy, the United States moves toward the peaceful integration of China into the global system while supporting the integrity of the system and U.S. interests. The United States as such avoids the pitfalls of regional withdrawal, alliance withdrawal, loose institution dependence, or regional alliance reliance.

There are three parts to this strategy (Nye 95). The first component is to maintain the United States’ forward-based troop presence, defending against a vacuum of power that would limit the possibility of China’s peaceful integration. The second is to reinforce U.S. alliances, confirming U.S. commitment to allies through word and action while confirming their reciprocal commitment. In doing so, we will better benefit from out alliance investments, and ensure cost sharing for the maintenance of security while promoting stability and continuity during China’s ascendance. This is being accomplished, in spite of a decreasing military size, through efforts such as changing the posture from a 50-50 Pacific-Atlantic split to a 60-40 Pacific-Atlantic split. The third dimension of this strategy is one of continued and increased support for regional institutions, complementing American alliance leadership. As a component of a broader strategy this effort will support confidence building between the U.S. and U.S. allies, and as well as between China and other regional actors.

From this foundation, designed in relation to this piece’s dismissed strategies, the United States can more specifically address China through a hedging strategy inspired by Armitage, Zoellick, and the descendent 2006 National Security Strategy. This China strategy aims to influence China’s policy choices and future evolution in positive directions, while guarding against the possibility of failure without becoming a self-fulfilling prophecy. Former Deputy Secretary of State Robert Zoellick’s approach, which emphasizes China’s potential as a responsible stakeholder in the international system, is broadly compatible with the engagement track of a hedge strategy. Conversely, the approach of former Deputy Secretary of State Richard Armitage, viewing China as a possible challenge to regional order, emphasizes the importance of the U.S.-Japan alliance in guarding against a potentially aggressive China.

Strategic Challenges

This Asia-Pacific strategy for the peaceful integration of China, though vetted against other options, is not without its challengers. Potentially the strongest challenge can be derived from Kupchan’s After Pax Americana: Benign Power, Regional Integration, and the Sources of Stability. Kupchan sees the decline of American hegemony globally and regionally (bar North America) as a foregone conclusion, asserting that, “Even if the U.S. economy grows at a healthy rate, America’s share of world product and its global influence will decline as other large countries develop and become less enamored of following America’s lead. Furthermore, the American electorate will tire of a foreign policy that saddles the United States with such a disproportionate share of the burden of managing the international system (Kupchan 40-1).” Building on his argument for the lack of long-term viability of the aforementioned Asia-Pacific strategy, Kupchan asserts that the leadership of the U.S. is holding back the Asia-Pacific from the stability it could achieve in the long term: “Although America’s presence in East Asia is indispensable, the particular nature of U.S. engagement also has high costs: it impedes the intraregional integration essential to long-term stability. American might and diplomacy prevent conflict, but they do so by keeping apart the parties that must ultimately learn to live comfortably alongside each other if regional stability is to endure (Kupchan 62-3).” In limiting regional integration, this scenario would ostensibly hold China back from peaceful integration.

It follows that the United States must move away from an active leadership in the Asia-Pacific. Kupchan recognises the comparative instability of a multilateral system, and as such asserts the importance of developing what he calls a benign unipolarity in East Asia under East Asian powers (Kupchan 42). However, even assuming that an active presence by the United States is not worth the cost or is not effective for China’s peaceful integration, there is simply a dearth of other options. Kupchan suggests the viability of the Sino-Japanese coalition, but affecting the coherence of a pluralistic core in the Asia-Pacific is a formidable task that will not be accomplished any time soon. Tensions have been building between these countries for the past several years, emerging as a Chinese security concern through aggressive government statements, as a Japanese security concern through increasing Defense White Paper analysis and as a public concern in recent clashes over the Senkakus/Diaoyu.

Conclusion

U.S. leadership supplemented by both engagement and balancing serves as the best U.S.-Asia strategy for the peaceful integration of China into the global system. Not only would the four other options reviewed (regional withdrawal, alliance withdrawal, loose institution dependence, or regional alliance reliance) create security risks, limiting China’s peaceful integration, but they would also not serve to defend U.S. interests to the fullest degree possible. While concerns remain about the U.S.’s long-term capacity to commit to the Asia-Pacific long term, the primary alternative of Japan-China leadership is simply untenable. The relationship of these two powers has to be fixed and both states would have to address their own issues before such a possibility could be considered. This analysis affirms the theoretical foundation of the pivot or rebalancing. However, proper implementation of this strategy is not yet set in stone, requiring continuous examination by the U.S. government and external consultants (e.g. U.S. Force Posture Strategy in the Asia Pacific Region: An Independent Assessment). China’s pressing rise will take strategic analysis further from a theoretical discourse and closer to a tangible measurement. It will become even more important in the coming years that the United States gets the strategy for China’s integration right.