The Fed and IMF again downgraded US growth projections, as they have done repeatedly for the last five years.

When the Federal Reserve and the IMF downgraded their forecasts for the US’ growth in 2014 last week, both bodies pointed to the terrible winter weather (that brought the term ‘Polar Vortex’ into the nation’s vocabulary) as the source of the revision.

Even though the US economy is expected to continue growing at previously forecasted rates for the rest of the year, the 0.1% contraction in the first quarter will hurt 2014 growth.

The Federal Reserve continued to drawdown quantitative easing, signaling that it is not worried about the country’s economic fundamentals. The IMF shows slightly more concern, predicting that employment and inflation would remain below target levels until 2017.

Taken as an isolated incident, these downgrades are not necessarily predictive of the fundamentals of the US economy. The Polar Vortex was a one-time shock that stunted demand and pushed inventories artificially low. In that sense, the forecasts are innocuous: there is no signal about the state of economy.

But downward revision of growth is becoming a regular occurrence from major economic forecasters. Every year since 2009, the IMF has overestimated the growth of not only the US but also of Europe and the world.

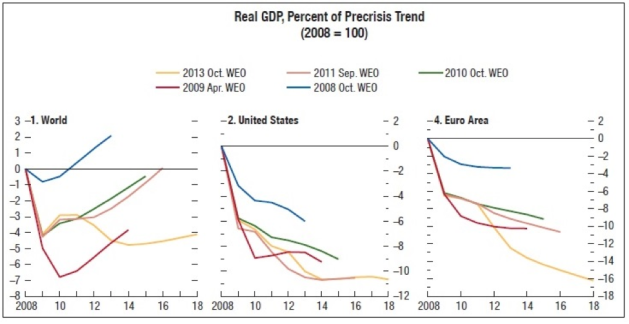

Since the end of the financial crisis, the IMF has consistently overestimated GDP growth. Each subsequent GDP forecast has fallen further from the pre-crisis trend. Source: IMF World Economic Outlook 2013

The graph above shows the IMF’s forecasts from 2008 to 2013 of the real GDP level compared to the growth trend before the financial crisis. Since 2009, when economic prospects looked dour, these forecasts have consistently been too optimistic. In 2010 and 2011, the IMF projected the world to catch up to the pre-crisis GDP trend by 2015. Now, it projects that world output will still be 4% lower than the pre-crisis trend in 2018. The story is similar, even if more gloomy, for the US and Europe.

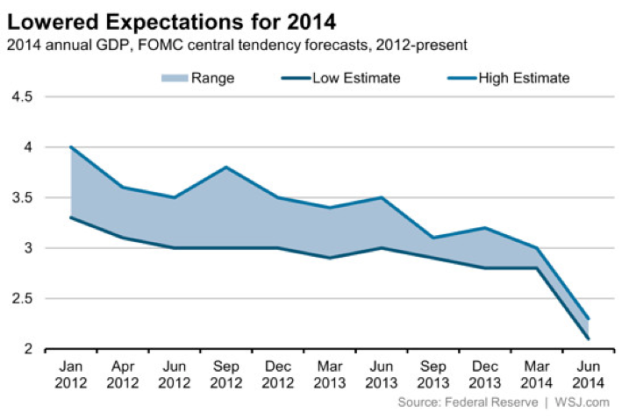

The Federal Reserve has fallen into the same trap of egregious optimism. The FOMC has been making projections on 2014’s growth since 2012, and their expectations have been revised downward with each Fed statement, most sharply in their June statement.

The Fed and IMF are staffed by some of the strongest economists in their fields, so why do they consistently get it wrong?

1) Forecasting is hard

Economist John Kenneth Galbraith quipped that economic forecasting only existed to make astrology look respectable. Even with the robust DSGE (and other types) of models that macroeconomists have developed, unpredictable shocks and unaccounted-for frictions can put a large gap between predictions and reality. Some of this unpredictability is inevitable, but it also may be that these bodies are mis-selecting their models.

2) Liquidity trap persists longer than expected

When the economy is in a liquidity trap, as in 2008-2010, output shrinks, unemployment stays high, and traditional monetary policy becomes ineffective. Without a major shock to expectations – like quantitative easing or forward guidance – or directly to output – like the 2009 stimulus – economies wallow in low growth and high unemployment.

But for whatever reason, the policy measures taken were not robust enough for the economy to escape the cycle. It is even a question whether the economy is still on the edge of a liquidity trap. The US started its fiscal contraction too soon, leaving the Fed with too high of a burden to reasonably carry in reviving the economy.

But under pressure from hawkish Fed Governors like Charles Plossner of Philadelphia, the Fed may not have taken enough steps to bolster the economy, as Minneapolis Fed President Narayana Kocherlakota has repeatedly suggested. Other options on the table include price-level targeting, nominal GDP targeting, and continued quantitative easing.

3) Economic fundamentals changed under our noses

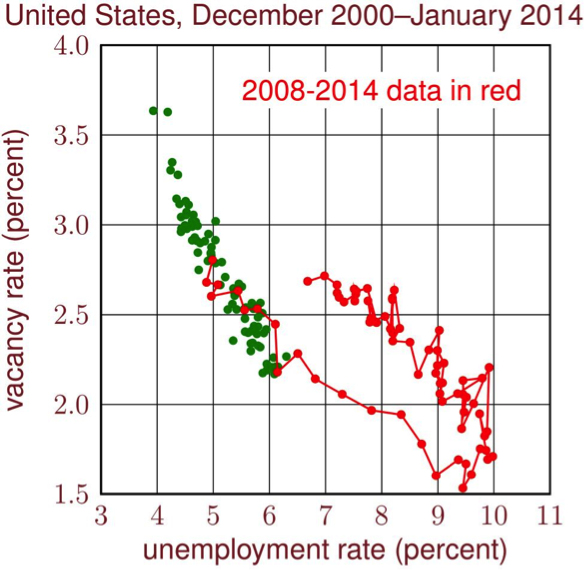

The Beveridge curve is the statistical relationship between unemployment and job vacancies: in the data, the fewer the job vacancies, the higher the unemployment. Presumably, the Fed and IMF look at a Beveridge curve – or at least implicitly think about one as they are forecasting. As job vacancies have ticked up in the last three or four years, most economists would see that as a precursor to a drop in unemployment.

That drop in unemployment – particularly in alternative measures of unemployment – has not happened. The Beveridge curve that we’ve observed for decades may have shifted, showing that the economy is fundamentally different than it was in 2007.

The Beveridge curve since 2000. The rightward shift since 2008 may be a cause of the Fed and IMF’s overly optimistic. Source: Robert Shimer, University of Chicago

The reason is hard to pin down, but if it has shifted then policymakers have been using inaccurate forecasting tools. If this shift is permanent, it would necessitate a change by forecasters. If it is just temporary, then it still requires acknowledgment in the short run.

Working under old assumptions could explain the systematic errors in forecasts by the Fed and IMF, which has led to a more widespread belief that recovery is near and extraordinary policy measures can be slowed more quickly.